As a fellow contributor and Canadian, Kathy Steinemann puts it: “Over the years, I’ve interacted with Sam Kandej, an Iranian teacher, translator, and writer. He’ll be releasing a fiction anthology this summer, titled “Bike Killer.” Each story, originally written in English, will be published in Farsi.” My experience is identical and like Kathy, I’m publishing Sam’s interview and my responses today. A link to Kathy’s interview is found below.

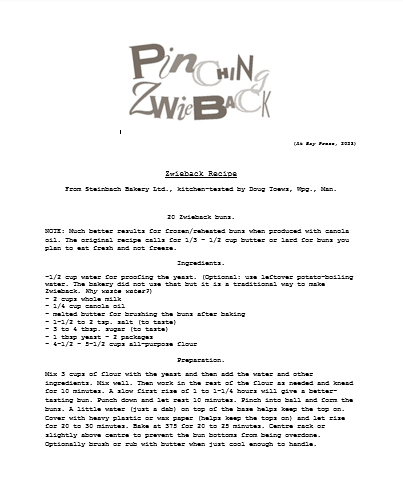

Sam Kandej of Iran asks English language author Mitchell Toews of Canada SIX QUESTIONS about writing. Mitch is the author of Pinching Zwieback (At Bay Press, 2023). He has a novel (also with Winnipeg’s At Bay Press) forthcoming this spring and a second collection will be introduced later in 2026, on Canada’s west coast. Mitch has a considerable periodical footprint with well over 150 publications in Canada, the US, the UK and elsewhere around the world. The recipient of a Journey Prize nomination and four Pushcart Prize nominations, Mitch has been writing professionally since 2016.

Mitch’s contributions for Bike Killer are:

Fast and Steep: First appeared in Riddle Fence magazine (CA, November 2019) and is also included in Mitch’s 2023 collection of short stories, Pinching Zwieback (At Bay Press, 2023). The Farsi version of Fast and Steep appears in “Bike Killer” by permission of At Bay Press.

I am Otter: First published in a print anthology, “Fauna” by The Machinery (India, February 2017).

The Seven Songs: First published online by Fictive Dream (UK, 2017).

Sam’s Farsi ebook will contain work by Ambrose Bierce, Doug Hawley, Suzanne Mays, Bill Tope, W. C. McClure, and Kathy Steinemann.

Interview:

1. What inspired you to start writing short stories, and what was it like seeing your first story published?

Why write? That really is a key question, Sam.

I returned to fiction late, after a working life in manufacturing and the building trade, then twenty years in advertising and marketing. As I neared sixty, I felt an urgency I couldn’t ignore — partly ambition, but more the sense that time was narrowing. Writing mattered to me, and I wanted to do it seriously: to learn the craft and commit myself to it. I carried a lifetime of experiences — work, family, failure, compromise, and joy — and I wanted the chance to express them honestly, in my own voice.

Short fiction became the natural form. Short stories allowed me to engage immediately and bring lived experience to the page. Submitting to journals and contests wasn’t just a route to publication; it was a way to enter a public conversation and learn through dissent, criticism, and occasionally, success.

Over time, and through many refusals, I am beginning to understand what stories really do. They entertain, but more importantly, they apply moral pressure. They place characters in demanding situations — often drawn from the author’s life — and allow actions, rather than explanation, to reveal who those characters truly are. I’ve learned that depth comes from brief, revealing moments that expose both strength and weakness and invite empathy.

When my first story was published, I was surprised by how quickly it stopped being mine. Once others read it, the story belonged to them, shaped by their own experiences and interpretations. That realization startled and humbled me — and lent direction to why I write: not to control meaning, but to share something honest.

~

2. Do you have a daily routine for reading and writing? What are some of your writing habits?

I don’t keep a rigid writing schedule. My days are often shaped by season and weather; living in a sparsely populated boreal forest comes with obligations that can’t be postponed. Even so, I write or edit most mornings. I pay little attention to the clock or the calendar, except to prioritize the work in front of me. Tasks like submissions, marketing, and organizing readings happen around that, as time allows.

Reading is constant. I read a large volume of short fiction, though lately I’ve been returning to novels. Some of my reading is professional — judging, writing blurbs or reviews, responding to advance copies — and that inevitably shapes what and how I read. I’m attentive to work that instructs or inspires, especially prose that shows me another way of handling voice, structure, or restraint. Reading for pleasure, along with literary events and conversations, tends to happen in the evenings.

I also write poetry freely and without expectations. I find it helps my mental state and sharpens my prose. Similarly, I often reread work I know well to reconnect with what I learned from it earlier. Miriam Toews’s novels, for example, remind me how courage and clarity can coexist on the page. Hemingway’s Nick Adams Stories continue to teach me how action and description can carry emotional weight without explanation.

When I write, I draft with minimal restriction, guided by a broad underlying plan. I revise rigorously. I read my work aloud and also use text-to-speech to hear it read back to me — usually both. Sound and rhythm tell me more than the text alone and this is particularly important for dialogue. I rely on editors and trusted early readers whenever possible. I enjoy editing almost as much as writing, though both require patience and stamina.

~

The title, BIKE KILLER, is taken from a Doug Hawley story of the same name. Doug is a tireless, loquacious, and talented observer of the human condition, who has left his charming and curmudgeonly tracks all over the internet in places like Fiction of the Web and Literally Stories.

~

3. When you’re crafting a story, do you write primarily for yourself or with a specific reader in mind?

I’m often aware of an audience, and that consciousness inevitably shapes the work. At the same time, I resist writing toward an answer or conclusion; I’m more interested in delivering an honest depiction. That tension means the unspoken demands of my imagined audience may go unanswered.

Frequently, the person or incident that inspired the story becomes the focal point, and I try to work from that individual’s perspective — filtered through my own experience.

Not all audiences are a single person. Some stories are projected more broadly; others begin as messages for a narrow audience but, through allegory, expand into a conversation with many readers. In the Bike Killer anthology, “I am Otter” illustrates that transition.

I am drawn to the lives of underdogs — marginalized people with little power or influence. Their experiences are among the most compelling, and their circumstances and responses often reveal something essential about life and human interaction. I’m repeatedly surprised and moved by the weight of choices made in everyday relationships and encounters — at a gas station, in a coffee shop, in the course of an ordinary day. Decisions that can alter lives, even if they seem mundane, form the substance of heartfelt and relatable prose.

~

4. Which one is more important to you: creating fictional characters and worlds or expressing your thoughts and opinions explicitly through writing?

Sam, I think about this question constantly as I write. I want my characters to invite engagement. They are often underdogs or misfits shaped by forces larger than themselves. Duality is also central to my work: there are rarely pure heroes, pure victims, or pure villains. Hope, however, is a constant, especially when it’s faint or contested.

“The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it” is one way to express this—a universal ethos that resides across belief systems.

The worlds I create are naturalistic and drawn from lived experience. They function as the moral atmosphere of the story rather than as mere setting. Whether rendered realistically or allegorically, these places reflect physical, social and cultural climates I know, which allows me to describe them honestly—sometimes to honour them, sometimes to expose them, and often both at once.

Readers are not students. I don’t write to dictate opinions. I want readers to enter a fictional life and leave with their own feelings, questions, and conclusions. That exchange builds the all-important connection between story and reader.

~

5. As a writer, do you primarily focus on problems or the solutions? Do you think a writer’s stories should be like a mirror to reflect humans’ deeds or a magical portal to take them to the place they should be in real life?

Problems vs. Solutions

Stories hinge on conflict. We create characters who encounter problems and watch them attempt to solve them. Often, instead of allowing a reasonable action to result in a solution, I insert yet another difficulty. These obstacles generate anxiety and empathy in the reader, deepening their emotional involvement in the character’s progress. The long-running American television series Stranger Things followed this pattern.

I seldom go to the full extent of nihilism, choosing instead to end with a solution—or at least a hopeful note. A grinding, unrelenting sequence of problems—like those found in Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy or a Dostoevsky novel—can be a gripping experience, but it risks fatiguing the reader. It’s also a hard style to master.

In writing, there can be no easy solutions; they are boring. What good is the most elegant solution if it is not entertaining? Rising anxiety allows the reader a satisfying sense of relief when a solution is finally earned.

Mirror vs. Portal

I am drawn to realism, so the “mirror” is my foundation. At the same time, there is power in describing a series of trials as we follow a heroic character through challenging circumstances—the “portal.” My forthcoming novel offers a hybridized blending of both. The youthful main character runs away from his problems and broken loyalties only to encounter new ones. He has intentionally put himself in a predicament, and his true test becomes his struggle to persevere. As he begins to adapt and grow, a new antagonist enters. This unfamiliar, disruptive and chaotic individual represents the greatest ordeal of all. In the end, despite many failures, the protagonist achieves some victories. He has transformed himself, but he remains flawed; his journey must continue. (Mulholland and Hardbar will be published in 2026 by At Bay Press. “Like ‘Fargo,’ but with German accents.”

~

6. If you were to teach a one-semester course on writing short stories, what would the essential pillars of your curriculum be? Is there a specific story, exercise, or piece of craft advice you’d build the entire class around?

Another question with depth. To answer this as honestly as I can, I must admit that I’m not sure I would make a good teacher of short story writing.

My rules would be less than rigid and also hard to interpret. I might write a different set of suggested approaches tomorrow.

With those undulating disclaimers in place, I might suggest the writers first imagine a place they know completely. It may be entirely imaginary, or completely real so long as the writer knows it well.

I could recommend that the story be based on a striking scenario from the author’s lived experiences. Fiction affords the freedom of creativity—freeing for both writer and reader so that the truth becomes malleable and the author may resculpt as they wish. In this case, the goal may not be morality or principle, but a memorable, engaging story. A beautiful—or wrenching—question the author asks the reader to consider.

I would ask my students to inject vivid life into the story at many points. We are physical beings; describe your characters’ abilities, failings, strengths, and peculiarities. Bruise us, enmesh us in our senses and emotions, put us in the action, feeling and being transported.

People talk. Share these discussions and ensure they sound real, as if a door swung open to bring us into the middle of a heated argument or an embarrassed confession, or a plea for mercy… until the door closes and shuts us out again.

Edit. Reading aloud, trim ruthlessly and with the urgency of a surgeon who knows to cut deep, often, and with precise intent. More than you think you should. More than you want.

Do not make yourself a hero or a victim in the story. Simply be a human describing the life of humans. Write of flaws. Dashed hopes, brittle egos, surprising valour. Show us answers seldom and yet keep alive our desire to seek them.

Thanks to Sam for including me. I am thrilled to be in BIKE KILLER, in the company of many wonderful writers. See Sam’s interview with Kathy Steinemann, HERE: https://kathysteinemann.com/Musings/kathy-steinemann-interview/

Image: The Nightingale and the Rose, used here to symbolize the Persian love of literature.