“But words are things, and a small drop of ink,

Falling like dew, upon a thought,

Produces that which makes thousands, perhaps millions, think.”

—Lord Byron (1788-1824)

This posting was edited and updated on September 25, 2024.

(Photo: Rob Fast)

Note: some of the images and statistical details in this article contain sensitive content.

While preparing a study session article for my writing group (the Write Clicks) about “Writing the Other” with my focus on older adult characters, I take a break. I slurp up a bowl of plain yogurt mixed with turmeric, organic blueberries, and hemp seeds. It’s a snack few people below a certain age—I’m unsure of what that age is, precisely—would eat. Pretty sure I would not have eaten this slop in 1974.

I pause, mid-antioxidant, in front of the TV where a 25-year-old woman discusses how she feels isolated because of her age. She feels old. Oh?

There it is. “Age” in all of its imprecise, vague, fluid, and ambiguous glory.

The woman, one many would readily term a younger woman, is a U.S. Olympic figure skater and her presence on the team is, in statistical terms, an anomaly. The 25-year-old figure skater feels “old,” even though— only days later—a 35-year-old woman wins gold in speed skating.

Context is everything.

For our writing, how do we define the terms: Old, Older, Older Adults (AP and other style guides’ preferred term), Older Persons (another benign choice), Older Writer, Older Author, Older Artist, Elder, Elderly, Aged, Senior, etc.? I’m not sure if any clear-cut definitions can be applied.

While definitions are tricky and may not be necessary, it’s important to use words that describe individuals and groups accurately and without bias or inference, intentional or otherwise.

To be honest, I began this process—researching and preparing an essay on age and ageism in writing—with a sense that I was a part of the stigmatized cohort and therefore had an intuitive, insider perspective. I am a 66-year-old (born in 1955) emerging writer and I have experienced many of the negative situations older people commonly endure. I frequently find examples on “writer Twitter” that are demeaning towards older emerging writers.

While all that is true, it’s also true that there are many others who suffer far more than me. Those who are older than me (not all but some); those who struggle financially, older adults with serious mental or physical health challenges, those who live alone or reside in remote locations or those in regions where exploitation, neglect, abuse, and violence towards older men and women is endemic—all these tolerate more than I. And what of older individuals who also are part of other marginalized, stigmatized, or mistreated groups?

I also need to confess that deeply embedded habits and preconceptions still live on in me despite my recognition of my own advancing age and despite my best intentions. My personal age bias persists. With respect, I suggest you check your own—I’d be surprised if you didn’t find that you too have entrenched beliefs and your vocabulary is rife with problematic (maybe even ageist) word choices. Our society has entrenched in us a vernacular of systemic bias towards older populations.

That’s the point, isn’t it? To become aware of the insidious microaggression of “slings and arrows1” and to stop their proliferation in literature. Ideally, we will embrace better choices and enact our own individual programs to stop the underlying mindset that gives permission to ageism.

I. Acceptability. “Is that okay to say?“

An Uncomfortable Sag

Certain phrases and once socially acceptable sayings most people today to experience feelings… Feelings that extend beyond the superficial message in the statement. Take for example, “That’s women’s work.” Say it aloud to yourself. Feel it? An uncomfortable sag in your mood? Depending on your point of view, your feelings may run from “So what?” to “How the eff could that ever have been acceptable?” For most today, I believe, this obsolete, misogynist phrase never was-never can be acceptable. It was insidious and powerful in its time and those who used it as a verbal weapon knew what they were doing. What they were really saying had to do with their view of order: “Males are superior; females are inferior.”

Now, what about age and ageism, today? My observation is demeaning stereotypical statements concerning older adults are not only common but are often given tacit permission and validity by tepid or nonexistent rebuttals. Where is that “uncomfortable sag” when we hear someone described as “just an old fool?” This slur implies that most older adults suffer from dementia, or what used to be called “senility.” And, while we’re on the topic, the etymology of the word “senility” is derived from an ageist source:

Like gender bias, age bias has many false comforts built into the language; into the mindset. Our society still stubbornly accepts most ageist stereotypes as truth. We are conditioned to allow this.

- “He’s just having a senior moment…” Stereotyping: seniors lack mental acuity.

- “Well, I think it’s just ADORABLE to see her try to waterski!” Condescension or belittling behaviour: treating older adults as if they were children. Another example, one that takes sharp aim at appearance and our enslavement to youth is the title of Editor/Contributor Rona Altrows’ collection of essays, short stories, and poetry, You Look Good For Your Age. Discussing the original idea for her book, Ms. Altrows writes:

“I returned to the same respiratory therapist for my annual checkup. I told her that her words to me, ‘You look good for your age,’ had inspired a book. ‘Wow!’ she said. ‘You wrote a whole book about that?’” —You Look Good For Your Age, The University of Alberta Press, https://www.uap.ualberta.ca/titles/985-9781772125320-you-look-good-for-your-age

“Blue Hairs… Porcelain Hips… Silverbacks.” Caricaturing: Using insulting names like these or “geezer,” “old fart,” “old bag” to let a perceived attribute or broadly applied characterization represent an entire group of people.

- Even more deplorable are these two aces in the caricature deck: “Angry Old Man” and “Crazy Old Lady.” These two pejoratives herd all ages and personalities into a single, stigmatic “type” that is at once degrading and handily gender specific. These objectional phrases in fact draw few actual objections.

- Then there is the everyday salad bar of feckless labels… A plethora of crudities, code-words, and depricating blanket descriptors:

- stingy, creepy, smelly, unpleasant, needy, baffled by technology, slow-witted, simple, demented, senile, incompetent, weak, slow-moving, unfit, has-been, stuck in the past, indifferent, uninformed, uncool

- foolish, naive, argumentative, obstinate, ultra-conservative, troublesome, annoying

- sexually inactive, unattractive or perverse (take your pick or choose column C: [] All of the Above)

Had enough? Me too.

Society has made progress towards de-normalizing negative language and attitudes towards women, and increasingly, towards other groups for whom a history of bias and discrimination exists: look at race, religion, sexual nature… So why is it seemingly still OKAY to malign older individuals?

Furthermore, how can we reduce the importance of age in our assessment of older people, without disregarding the positive aspects of age? How can we properly and appropriately recognize age and approach older adults as equals, albeit ones with a differing set of circumstances, experiences, and background references, among other things?

Once again we must ask, “who—exactly—are ‘the old?’” Finding one definition seems improbable. We need to incorporate individual, circumstantial factors.

Without fail and throughout our lives, every one of us is viewed as if through a constantly shifting kaleidoscope of age: Seen simultaneously by some as “old” and by others as “young.”

II. Diminishing Harm; Normalizing Ageism

Is ageism really that big of a problem? Does ageism compare to racism or misogyny or other societal bias and discrimination? If you really, really love your grandmother, for example, how could you possibly harbour ageist thoughts or sympathies?

Like me, I suspect many of you will start out with a “no-no-no way” self-assessment. Part of what is entrenched in systemic ageism are the diminishing arguments that seek to uphold what we’ve come to see as norms. So, please be wary of blinders you may have in place and take a hard look.

If we don’t honestly confront our own embedded ageism we won’t be able to keep it out of our writing.

“It seems to me that this determination by the non-elderly is a consequence of the death-denying culture in which we live, where youth is overvalued, the middle-aged control the world, and the old are perceived as useless, and therefore, better dead.”

—Sharon Butala (Officer of the Order of Canada) in “This Strange Visible Air – Essays on Aging and the Writing Life”

Butala is not alone in her unflinching appraisal. The Gerontological Society of America sees ageism as having its roots in a kind of hateful miasma, utilizing violent terms like “Coffin Dodger” and “Boomer Remover.” They see a condition in which,

“The rhetoric of disposability underscores age discrimination on a broader scale, with blame toward an age cohort considered to have lived past its usefulness for society and to have enriched itself at the expense of future generations.”

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32719851/

It’s worth reminding ourselves too that, according to the World Health Organization global study, “15.7 percent of older people—or almost one-in-six—are victims of abuse.”

—Global report on ageism https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240016866

The grief of older people and their plight in our society is greatly undervalued.

Older adults are unfailingly “young adjacent.” In the everyday workday life of older writers, specifically, there is no escaping to a separate generational safe room where ageism is non-existent. Older writers must operate in the presence of—and sometimes in spite of—those who may wish to denigrate, stereotype, and caricature older adults in their writing and express negative sentiments toward older writers in their writing practices.

2024’s Threads, said to be a “kinder, gentler” forum for writers recently contained a lengthy discussion on “old people” ending with a classic, phobic, toxic “some of my best friends are old and I don’t mind them,” comment from a self-described “young writer invested in life-long learning.”

A recent article in the Canadian literary source, Quill and Quire, stated that approximately 77% of the writing jobs in Canadian literature were held by those age 40 or less. (I don’t have a citation for this, but welcome a correction or a confirming citation.)

The artistic lives of older writers are inextricably interwoven with younger writers, editors, publishers, critics, reviewers, and others who have a say in our professional fate.

Lunatic Fringe?

Ageists are not confined to a small group of outliers. For a present-day, real-world indicator of the state of ageism and its potential for negative influence, consider the Covid experience, worldwide.

“Whether it’s the impacts on their own health or losing their jobs or the isolation or exclusion from treatments [COVID-19] has really shone a light on ageism,”

— World Health Organization (WHO) https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-03-19/who-finds-billions-suffer-from-ageism/100016688?utm_source=abc_news_web&utm_medium=content_shared&utm_campaign=abc_news_web

While older adults (statistically, slightly more men than women) are always going to lead the mortality percentages over more youthful cohorts—not surprisingly, age is a strong predictor of death rates—older Canadians had this statistical abnormality: in 2020, there was a statistical jump of 11,386 more deaths than the long-standing norm, for all age groups. Of these, the cohort of those age 65 or greater recorded 78% of those 11,386 anomalous deaths. This can be attributed to no other factor than Covid.

Covid has revealed a tear in our social fabric and is chilling to consider.

https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/coronavirus-disease-covid-19/epidemiological-economic-esearch-data/excess-mortality-impacts-age-comorbidity.html

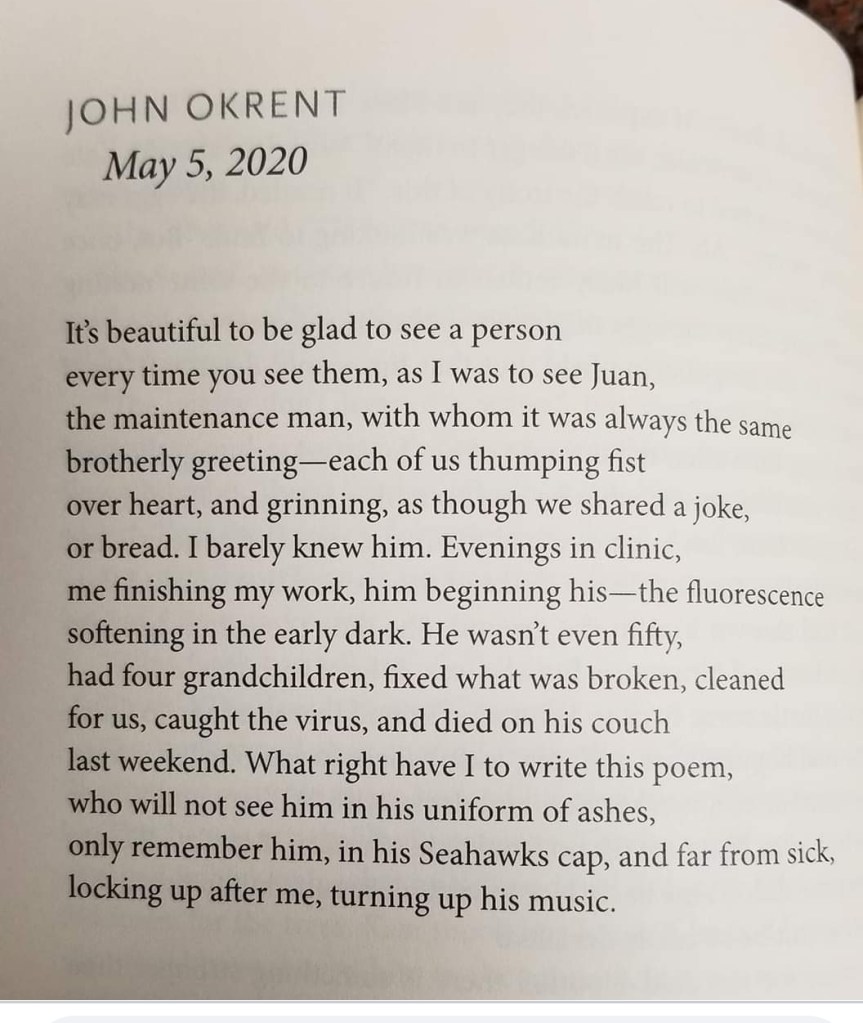

Furthermore, for the many older adults who also overlap certain other marginalized populations (experiencing the effect of intersectionality), there may be an even greater and more shocking comparative “excess” death rate. John Okrent’s moving verse touches on this and offers inspiration to us as writers.

Last, we would do well to remember that older adults represent a significant portion of the Canadian “patchwork quilt.” In Canada today, StatsCan estimates, “Almost one in five (18.5%) Canadians are now aged 65 and older.” This segment is growing—if we assess the number of older characters in Canadian literature today, will it reach 18.5%? Representation, as they say, matters.

https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/210929/dq210929d-eng.htm

Moreover, Saskatchewan Seniors Mechanism reports in Ageism and Media in Saskatchewan, that: “By the year 2050, it is predicted that the number of older adults will exceed the number of younger persons to reach approximately 22% of the world’s population”

—Abdullah and Wolbring 2013; Nosowska, McKee, and Dahlberg 2014

This situation cries out for our attention. It begs our activism as citizens first, but also as writers and communicators because we can so effectively lead by example, help to inform public opinion and drive change in popular culture.

“Ageism can operate both consciously (explicitly) and unconsciously (implicitly), and it can be expressed at three different levels: micro-level (individual), meso-level (social networks) and macro-level (institutional and cultural).”

—Determinants of Ageism against Older Adults: A Systematic Review

III. There are Many Negatives—What are the POSITIVES?

Negative media and gut-turning examples abound (see the images below, if you still doubt that) but we need some positive input to balance the scales and keep us from smashing all the dishware.

Strive for Positive Words

Avoiding negative communication is half the battle.

As artists, we must strive for positive words and phrasing. There is much to be admired in older adults and also in the uplifting canon of writing about elderly individuals. I cite John Okrent above and Old Man and the Sea a bit further on. Here are several other exemplars from my own bookshelf:

—The older characters in The Grapes of Wrath. Steinbeck’s characters, by the way, were drawn literally from real life. He embedded as a documentary journalist with a large group of migrants heading west and his The Grapes of Wrath characterizations were hybrids of the behaviour he witnessed first hand.

—Fight Night, Miriam Toews’ shining, unafraid story of an older woman living out the last joyful but complicated months of her life and the descriptions of her loving—but often fractious—family relationships is a superlative guide. It is an insightful, true depiction of a singular character who, more than anything, “wanted to be in the thick of things!” She did not allow systemic ageism or the social stigma of age or her physical challenges stop her.

—Moonlight Graham is one of my favourite literary characters. W.P. Kinsella brings the character to life in the novel Shoeless Joe. It’s a rich and complex template for writing about an older adult character.

[…] “That’s what I wish for. Chance to squint at a sky so blue that it hurts your eyes just to look at it. To feel the tingling in your arm as you connect with the ball. To run the bases – stretch a double into a triple, and flop face-first into third, wrap your arms around the bag. That’s my wish,”

—Moonlight Graham, in Shoeless Joe, discussing his dream to have an at-bat in a big league ball game

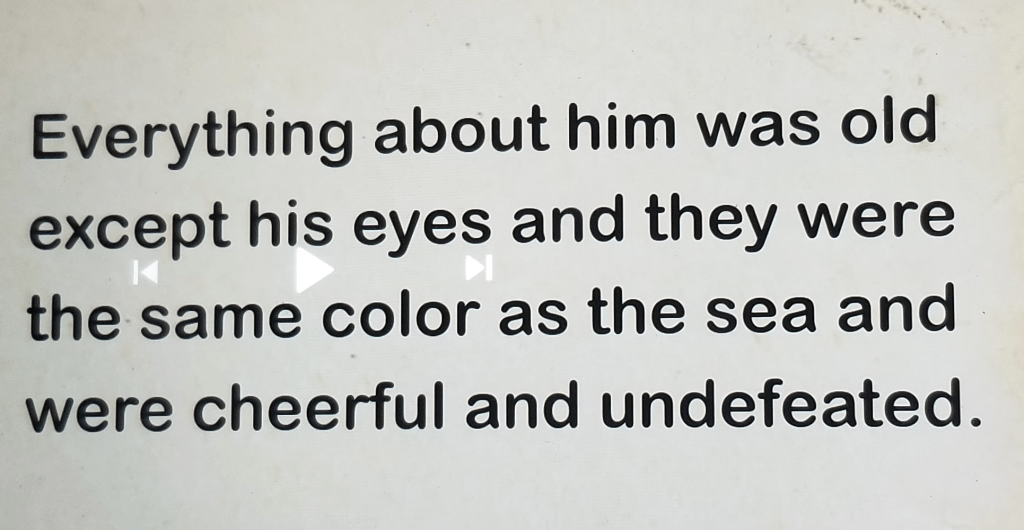

The Graham character expresses his wish, not in terms bound by time or constrained by a stereotypical view of an older person’s body, but rather from the viewpoint of a strong ballplayer, ready to take on the mental and physical challenges that create a definition of who he is. It’s how he sees himself and how we see him too.

—And yet, age is not imagined. Our bodies change and that can include our mental and emotional state as well. There’s no need to sugar-coat this or pretend that an end to life is not real. This must be faced for what it is. Who better than a poet to take this on?

[…] “You live a while and then time happens…

his knobbly hands

lying on the white sheet blue almost grey ridges of blood running

across his hand’s map his thin arms the pale blue top nurses tied in

bows at his back his brown eyes you could see through if you

weren’t afraid…“

—Patrick Friesen, The Shunning

—Here’s another moving example: an adult son considering his father’s later-life adversity. It is written with respect and honesty. An excerpt from Ralph Friesen’s lovely memoir, Dad, God, and Me.

[…] “(Mom) called the next morning to say that Dad had died…I hung up the phone, went to the living room, and picked out a Peter, Paul, and Mary LP from the stack on the table…The trio of voices, so harmonious, celebrated Stewball, the legendary racehorse: ‘Oh way up yonder / Ahead of them all / Came a prancin’ and a dancin’ / the noble Stewball.’ Tears started in my eyes; I did not know why. Today I think of the song as an ode to my father, who had always put himself second, who abjured dancing, who was humble and slow-moving. Now, released from his pain-body, he was a beautiful thoroughbred, dancing proudly, crossing the finish line first.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hXdQB-mR4tg

IV. If Only There Was a Style Guide.

In Gregory Younging’s brilliant, Elements of Indigenous Style – A Guide for Writing By and About Indigenous Peoples, the author covers the full spectrum of do’s and don’ts and (in my estimation) a few “Hell, NOs!” Older adults and those who write about/depict them could take some pages, literally, from Younging’s book.

Elements of Indigenous Style outlines 22 principles of Indigenous style. The author goes into detail and these tenets are specifically Indigenous, not “cookie-cutter.” It’s worth noting too that in Elements of Indigenous Style the seventh Principle is “Elders.”

“Indigenous style recognizes the significance of Elders in the cultural integrity of Indigenous Peoples and as authentic sources of Indigenous cultural information… Indigenous style follows Protocols to observe respect for Elders.”

Page 100-101, “Elements of Indigenous Style – A Guide for Writing By and About Indigenous Peoples,” Appendix A. Brush Education Inc. 2018.

Younging’s work concerning Elders, in particular, could be seen as a trailblazer and inspirational matter, and writers depicting older adults of all “race, creed, colour, and religions” can draw substance from this work.

A similar groundwork—an “Older Adult Style Guide” perhaps—is needed. Something with Elements of Indigenous Style‘s comprehensive nature; a Strunkian Elements of Older Adult Style.

Happily, such a guide DOES exist! In fact, more than ONE!

A Style Guide for Writing and Speaking

— avoiding ageist concepts and language

An excellent publication from nearby Saskatchewan is Words are Powerful. A link to the PDF and the website is included and I’m sure readers will find this to be an excellent source.

For this resource and more, please see Other Reading, below.

V. A Style Guide for Older Adult Characters, Scenes and Stories

[…] “analysis of past and present literature shows that the aged have been stereotyped and portrayed negatively. By not assigning them a full range of human behaviours, emotions, and roles, authors have categorized them, resulting in ‘ageism’—discrimination against the elderly.”

—Anita F. Dodson and Judith H. Hauser, “Ageism in Literature. An Analysis Kit for Teachers and Librarians.” 1981 (Sponsored by U.S. Dept. of Education.)

https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED211411

It’s cogent to note that the conditions found in the 1981 study cited above have not changed much. For me, this status quo suggests that if there are no rules, the lowest common denominator will continue to prevail for older adults in literature. (The biggest bully wins… well-known to schoolteachers, bartenders, and parliamentarians.) So, as a point of embarkation, here are a few basic ground rules for those writing about older adults as “the other:”

1. Examine your reasons: exactly why is it necessary for you to write for or about someone outside of your own experience, in this particular situation? Could this better be left for older adult authors to take on? #ownstory

Confession: I’m in the camp of wanting lots of writers to write about “the other;” about older adults. The more often older characters appear, central to the plot and treated as equals, the better.

2. Recognize and avoid “young saviour” syndrome.

3. Do your homework. Know the issues. Read older adult authors. Go to their places, meet with older adults, listen, observe, participate. Ask.

4. Review your draft with older adults. Consult with accredited individuals or those recognized by peers. (You might have to pay them.)

5. Assign older characters to main character roles and place them in a diverse range of occupations and settings.

6. Older adults do not necessarily see themselves as “OLD,” or at least, not entirely. Writers must capture this aspect of self-identification when they write older characters.

Sidebar: The Cojimar fisher upon whom Hemingway based the Santiago character was late forties-early fifties. So “old” as a definitive description is assailed once again. P.S. — Canadian Prime Minister JUSTIN TRUDEAU, who is often used as an example of youth, was born in 1971, putting him in his early fifties.

7. “Older Adults” is not a homogenous or coherent group*—it is as diverse as any younger group in all categories including AGE. Recognize and avoid cliched older adult tropes

8. Older people may not always want to be judged by “young” standards. Older adults are not “failed*” or “under-performing” young people, THEY ARE THEIR OWN DISTINCT COHORT. Furthermore, like other groups who are made invisible by prevailing bias and discrimination, older adults want to be seen as individuals and not just as an interchangeable part of a group or category.

*Concepts discussed by Sharon Butala in “Ageism Limits Our Potential” | Sharon Butala | Walrus Talks, May 29, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QE5M-3dZpks

9. Attack your own bias. Seeing, revealing, and dismantling your own personal prejudices will unlock a sense of honesty in others. (And free your writing from a disingenuous constraint.)

10. WHAT IS MISSING FROM THIS LIST?

VI. Conclusions

1. Ageism is unique and distinct from other similar social problems. At the same time, the approaches used successfully by other systemically marginalized groups can be considered and may be adapted to combat ageism.

2. Ageism is no less serious than other forms of discrimination or bigotry.

3. It is within the scope of art, including all kinds of writing, to uplift older adults and address ageism directly and at the source.

Other Reading:

1Treatment of the Elderly in Shakespeare

Shakiya Snipes

Denison University

Medical News Today

“What is ageism, and how does it affect health?”

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/ageism

Words are Powerful

A Style Guide for Writing and Speaking

— avoiding ageist concepts and language

Produced by the Ageism & Media Committee

Saskatchewan Seniors Mechanism

https://skseniorsmechanism.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/18-04-12-Words-are-Powerful.pdf

APA Style

Age

https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/bias-free-language/age

AP Stylebook

https://www.apstylebook.com/ap_stylebook/older-adult-s-older-person-people

Quick Guide to Avoid Ageism in Communication

Guidelines for Age Inclusive Communications

American Psychological Association Style Guidelines

https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/bias-free-language/age

“Report by the Centre for Ageing Better”

https://ageing-better.org.uk/sites/default/files/2021-08/Old-age-problem-negativeattitudes_0.pdf

Challenging Ageism: A Guide to Talking About Ageing and Older Age

Meta Dialogue Starters/Search Terms

- Intergenerational Relationships

- Unrepresentative Imagery

- Ageist Imagery

- Age-Positive Phrases and Terminology

- “Age-Loaded” Adverbs & Adjectives

- Do a word-search on one of your stories: “old”

One Last Thought… I’ve made over 700 submissions to literary markets in Canada, the U.S. and the U.K. since 2015. In my experience, I’ve seen ONLY ONE submission guideline that prohibits ageism by name: Agnes & True, see below. (If you find another, please place a link in the comments!)

More positively, here is the formal submission guideline from one of the largest circulation literary periodicals of the past three decades, Tin House. They address prospective authors in a Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion statement crafted with care and specificity.

“In particular, we are looking to engage with work by writers from historically underrepresented communities, including—but not limited to—those who are Black, Indigenous, POC, disabled, neurodivergent, trans and LGBTQIA+, debuting after 40, and without an MFA.”

As noted above, a Canadian literary periodical that is noteworthy is Agnes and True, which […] “celebrates the achievement of women…” and also states, “In addition, we are particularly interested in discovering and publishing the work of emerging older writers,” and “We also do not publish work that is racist or sexist or ageist or that would incite others to become racist or sexist or ageist. We reserve the right to define all the above-mentioned terms for ourselves.”

Agnes and True was kind enough to suggest another resource: Ageing Better Resource Space

I’ll also add that it is perplexing to see Agnes & True as the only Canadian literary periodical/journal/review that explicitly sets out age/ageism as intolerable. Winnipeg’s Prairie Fire recently took a bold step by publishing a (exceptionally popular) “50 Over 50” collection—a landmark, age-related moment in CanLit. (To be clear, men and non-binary individuals were not included in this submission call.)

I know from personal experience that there are numerous Canadian literary markets that accept work from older writers of any description. My hope is that they will soon feel comfortable enough to stipulate to this, in print, in their DEI statements.

(NOTE: The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms sets ample, legal precedent for publishers: discrimination based on age is prohibited in Canada.)

DEI Addendum

September 25, 2024: During my recent submissions and while prospecting for short story markets I came across these Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion statements in U.S. Publications. There appears to be a discernable surge in the number of top literary markets and affiliated organizations, universities, and other publishing bodies that explicitly specify AGE and AGEISM in their public DEI statements.

Besides Tin House, mentioned earlier, here are some “big market” American examples of how Ageism’s long reign as a covert, modern-day “scarlet letter” seems to finally be coming to an end:

“We are seeking writers whose work speaks to issues and experiences related to inhabiting bodies of difference. This means writing that centers, celebrates, or reclaims being marginalized through the lens of race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, age, class, religion, illness, disability, trauma, migration, displacement, dispossession, or imprisonment.” —Adina Talve-Goodman Fellowship, Brooklyn, New York

~~~

“Shenandoah aims to showcase a wide variety of voices and perspectives in terms of gender identity, race, ethnicity, class, age, ability, nationality, regionality, sexuality, and educational background (MFAs are not necessary here). We love publishing new writers; publishing history is not a prerequisite either. “ —Shenandoah Literary, Washington & Lee University, Lexington, Virginia

~~~

“The Paris Review is an equal opportunity employer. We evaluate qualified applicants without regard to race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, national origin, disability, veteran status, age, familial status, and other legally protected characteristics.” —The Paris Review, Big Sandy, Texas

~~~

“Furthermore, we’re interested in working against past and present inequities by publishing work by individuals from systemically marginalized groups, including writers of color, nonbinary and trans writers, members of the LGBTQIA+ community, neurodivergent writers, disabled writers, working-class and low-income writers, older writers, and all others who consider themselves underrepresented in contemporary literature.” —The Cincinnati Review, the University of Cincinnati

~~~

Sidebar: Cincinnati Review Managing Editor Lisa Ampleman further reported, “When we did a survey two years ago, attention to older writers was one of the major requests from those who took it.” (9.25.24)